How India and Japan have a history of material and philosophical trade on the most iconic trade route – The Silk Road.

The Silk Route was a term that came into the mainstream dialogue in the 19th century when German geographer Ferdinand Von Richthofen defined this ancient road winding through Asia. On account of the influence of Asian trade on International trade, it’s safe to state how the Silk Route was the most influential trade route in the history of mankind.

The specifics:

What is the Silk Route?

The route contains a complicated chain of roadways and seaways that connected the ancient world in a grand way. Humanity, traded goods, ideas, architecture, scientific discoveries, religious thoughts, philosophical musings, languages, spirituality, literature, artifacts, music, dance, food, drinks and cultural traditions moved through it for centuries. It also unfortunately aided conquests of plundering hordes, which either birthed empires, or sowed the seeds of destruction and destitution. It spanned over 7,000 kilometres and covered more than forty countries.

It was essentially a trade and diplomacy channel that ran through a network of land and water pathways spanning over China, Mediterranean countries, Near and Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent and East Asia. It contained primary roads, like the Oasis Route (4,000 kilometres) which connected all the acrid and semi-acrid regions of Central Asia to establish the East-West trade connect. It also contained secondary routes, like the Steppe Route, which extended the Oasis Route northwards and connected the rest of the Route to the Southern Sea Route, which contained ports at the China Sea, the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. It simultaneously had alternative roads, which were shorter, but were riddled with bandits and criminals seeking refuge like the route which began at the southern edge of the Taklamakan desert. Most of these roads met at Kashgar (Kashi, far west China) making it an important trade centre.

The Japanese-Indian Connection

All these routes are important to the Indian-Japanese trade connect because Indian goods ended up being traded at the Chinese ports to the West or the city of Nara. Through a complicated road that ran through the Taklamakan desert, the Tien Shan and Kunlun Shan, the Pamirs, the Karakum and Kyzylkum desert, and the Hindu Kush, the travelling caravan could finally meet the oceans to reach Japan or the West. The countries definitely have a connection that runs deep.

Japan and India have always been welcoming countries. Japan was the eastern end of the Route. India was to the centre (geographically), and given its peninsular nature, it was connected to four separate corridors of the Route.

The route that connected both countries primarily was the Southern Sea Route, which started at the Southern coast of China in Kuangchou (Canton), then it rounded the Indo-China peninsula through the Malacca Straits, and it connected to India at the mouth of the Ganga. At the mouth of the Ganga, traders exchanged all that they could, picked people up (or dropped them off), and carried on towards Japan.

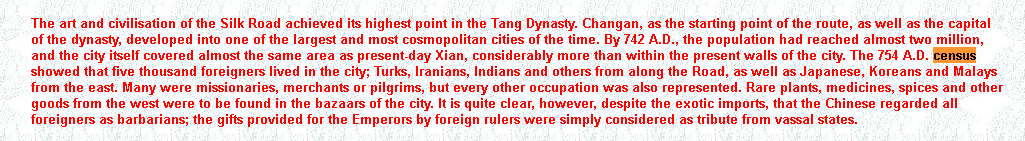

We know this because a Chinese (Tang dynasty) census conducted in 754 AD showed around five thousand foreigners living in Xian. These foreigners were Turks, Iranians, Indians, Japanese, Koreans and Malyas.

These foreigners were exiled aristocrats and army generals, healers, merchants, artisans, Buddhist monks, missionaries, scholars, musicians, dancers, artists, and refugees. As they moved around, they unconsciously spread the culture and tradable goods from all the different countries they visited.

As this economic and cultural pipeline deepened, Silk became the currency that prospered the Chinese economy. However, immigration across the Silk Route began suddenly. Silk tradesmen went to the Korean peninsula in 200BC, and they landed on Indian and Japanese shores in 300 AD. From then on, Asia became the place that traded Silk. In fact, the Romans knew of Asia as Seres or the Kingdom of Silks. Traders of other crafts also started immigrating in hopes of finding the next Silk.

At the beginning of the sixth century, the Japanese began immigrating to improve their overall skills and knowledge. Officials from the Royal Courts, students, and Buddhist monks went across Asia for training under the masters. The migration began from Osaka and evidence of this can be found in the archives of the monastery of Hōryū-ji (法隆寺)and the imperial treasure-trove of Shōsō-in (正倉院). Indian specialisation regarding trades like extracting poisons using medicinal plants, processing and dying cotton to make colourful fabrics, and Buddhism moved seamlessly from India to Japan. Kyōtarō Nishikawa’s book, ‘The Great Age of Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, AD 600-1300,’ paints a vivid picture about the positive relationship between the two countries.

Buddhism and how it links India and Japan

Buddhism, like most religions, attracted the wise, insightful people of each region it graced. Buddhist monks meticulously tabulated data while also facilitating translations for everyone willing to learn. They let people communicate with each other

The Kushan rulers of India were so fascinated by their Japanese counterparts that they wrote about the cultural relations they had with Japan fondly. They also fostered common cultural values to build up companionship with their new allies.

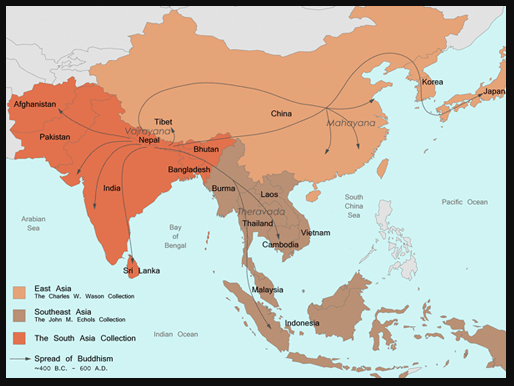

India is where Siddhartha Gautama (“the Buddha”) attained enlightenment. His disciples brought his teachings to China in the 1st century AD. These disciples also travelled to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Xinjiang, China, Korea and Japan. Given their peaceful nature and message of love, they were allowed to build monasteries and pagodas in all the Silk Road towns.

The Buddhist monks who travelled extensively shared and imbibed cultures. They traded or gifted pieces of art, sculptures, figurines, and lots of literature to emperors, chieftains and religious heads.

When the Han Emperor Mingdi (漢明帝) dreamed of a golden figure in his dream, Chinese diplomat Zhang Qian had returned from Ta-hsia (大夏), with tales of a golden figure preaching in Tien-Chu (India). General Cai Yin was sent to Central Asia to learn more about the golden figure. Three years later, when he returned, China heard about Buddhism for the first time. Two Buddhist monks She-mo-teng and Chu-fa-lan accompanied the General on his way back to China. Buddhism spread through China like the fragrant wisps of an ethereal incense stick.

By the time 4th century rolled around, Buddhism had spread all across the Route courtesy of translation efforts by Translation Bureaus. Indian Buddhist monk Kumarajiva formed a team which translated some 98 works of Buddhism to Chinese and other languages.

These monks practiced Hinayana and Mahayana forms of Buddhism. It is the Mahayana form of Buddhism that links India and Japan. Mahayana literally translates to ‘a large vehicle.’ Mahayana Buddhism quickly replaced the Hinayana schools on the Silk Road because of how popular the doctrine became.

As the principal trade route in India passed through India’s premier education hub Taxila, onward to Central Asia, a lot of Indian culture and knowledge just transmitted everywhere. Some of these scholars sailed to Japan around 8th century via the port in the then capital of Japan, Nara.

Emperor Shōmu (聖武天皇) ruled over Japan in the 8th century. He believed in fostering new cultures. His royal court preserved every record and artifact meticulously, and they enabled the spread of Buddhism in Japan, a country that prayed to Shinto Gods.

Unlike the rest of the world, which adopted a new religion by discarding the religion they previously practiced, Japanese scholars incorporated Buddhism into their religious Shinto faith. In fact, they had an Indian monk Bodhisena (菩提僊那) perform the first Nichiren Eye-opening ceremony (開眼供養) of Lord Buddha at Tōdai-ji. Bodhisena was joined by various Chinese, Korean and Japanese monks in this sacred ceremony of painting Lord Buddha’s pupil.

The clue of our relationship lies in the artefacts and documents, meticulously protected at the Shosoin Repository by the members of Todaiji and the Imperial Household Agency. Todaiji’s architecture is modelled after Chinese architecture. Animal motifs not found in Japan like peacocks, elephants, tigers show up in the artefacts stored in the repository. Also, ivory, sandalwood, precious and semi-precious gemstones not native to Japan, but native to India can be found in the repository. Similarly, a silhouette of the Shinto deer, the symbol of the Kasuga Taisha (春日大社) can be found in records of Hinduism showing how the cultural significance of the deer and their status as sacred messengers carried into India and Central Asia.

A very visible symbol of Indo-Japan friendship is Daruma-san (達磨). This red and white stripped hollow doll, provides the patience and luck required to help achieve our goals. Historically, it was modelled after Bodhidharma, the Indian Zen-Buddhist monk. He was the third son of a Pallava king from Kanchipuram, India who brought the art of zen to all of Asia (around the 6th century). His words impressed the Emperor Shōmu and Empress Kōmyō so much that they lived by the principles he preached. In fact, they were the first Japanese royalty to retire from their royal duties to become a Buddhist monk and a Buddhist nun respectively. References to Bodhidharma and his disciples can be found across museums and temple archives in Japan.

Japan has such a welcoming spirit that they even welcomed Hinduism with open arms. Scholars from the Age of Kukai (774- 834AD – the founder of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism), report the origins of Ganesh worship in Japan since 806AD. In Japan, Lord Ganesh is Ganesha/Vinayaka/Kangiten (歓喜天, “God of Bliss) and like the Indian Ganesh, the Japanese Kangiten also offers good luck, love, enlightenment and worldly gains. We also find the idols of Benzaiten (Goddess Saraswati, 弁財天) and Bishamonten (Lord Kubera, 毘沙門天) in the temple at Daisyō-in. Similarly, the Indian God of death, Yamraj, became Yamantaka, something that death (Yama) feared.

What now?

As Japan now invests 130 billion ($1.89 billion) in the ‘Look East’ policy of India to help develop the infrastructure of North-Eastern India under the “India-Japan Coordination Forum for Development of North East,” it just highlights how Japan has always been welcoming and helpful to those who seek their assistance. All we have to do is look around with open eyes and soak in the glory of the cultural juxtaposition provided by the glorious trade route that we dub the Silk Route.

I won a prize for this article. Unfortunately, the platform in question hasn’t survived the pandemic.

If you enjoy my content, consider signing up to my monthly (free) newsletter. If you have any insights, information or opinions about this piece, feel free to let me know in the comments.

The Writing Catalogue

Ideas, Words, Bestsellers

This article just made me travel the ancient silk route.

Very informative.

Helped me know things in a nutshell.

I am glad to have your seal of approval.

Write something about Japan for us next. I can’t wait to read what you have to share! 🙂